This post offers different examples of data visualisation aimed at exploring “State of the Union” speeches since they have first been introduced in 2010 (the speech was not delivered in 2014 because of European Parliament elections). It highlights key steps in the procedure, and includes the actual code in the R programming language used to create them (hidden by default).

The source document can be downloaded from GitHub.

Downloading the speeches

The full transcript of the speeches is available on the official website of the European Union. Here are the direct links to each of the speeches:

| Year | President | Link |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Barroso | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-10-411_en.htm |

| 2011 | Barroso | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-11-607_en.htm |

| 2012 | Barroso | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-12-596_en.htm |

| 2013 | Barroso | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-13-684_en.htm |

| 2015 | Juncker | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-15-5614_en.htm |

| 2016 | Juncker | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-16-3043_en.htm |

| 2017 | Juncker | http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-17-3165_en.htm |

In order to process them as data, it is necessary to extract first the relevant sections of the webpage. The same could effectively be accomplished by copy/pasting the transcripts.

Word substitutions

In order to analyse texts, it is common to stem words to ensure that “example” and “examples” are counted as one and the same word. Rather than stemming all words (which would make some of them unclear in the graphs that follow), only selected keywords are stemmed (e.g. ‘citizens’ is transformed to ‘citizen’, and ‘refugees’ is transformed to ‘refugee’). Self-referential words such as ‘european’, ‘commission’, ‘union’, and ‘eu’ are excluded from the following graphs: they are found much more frequently than all others and would effectively obscure more interesting results. Stopwords such as ‘and’, ‘also’, and ‘or’ are also excluded.

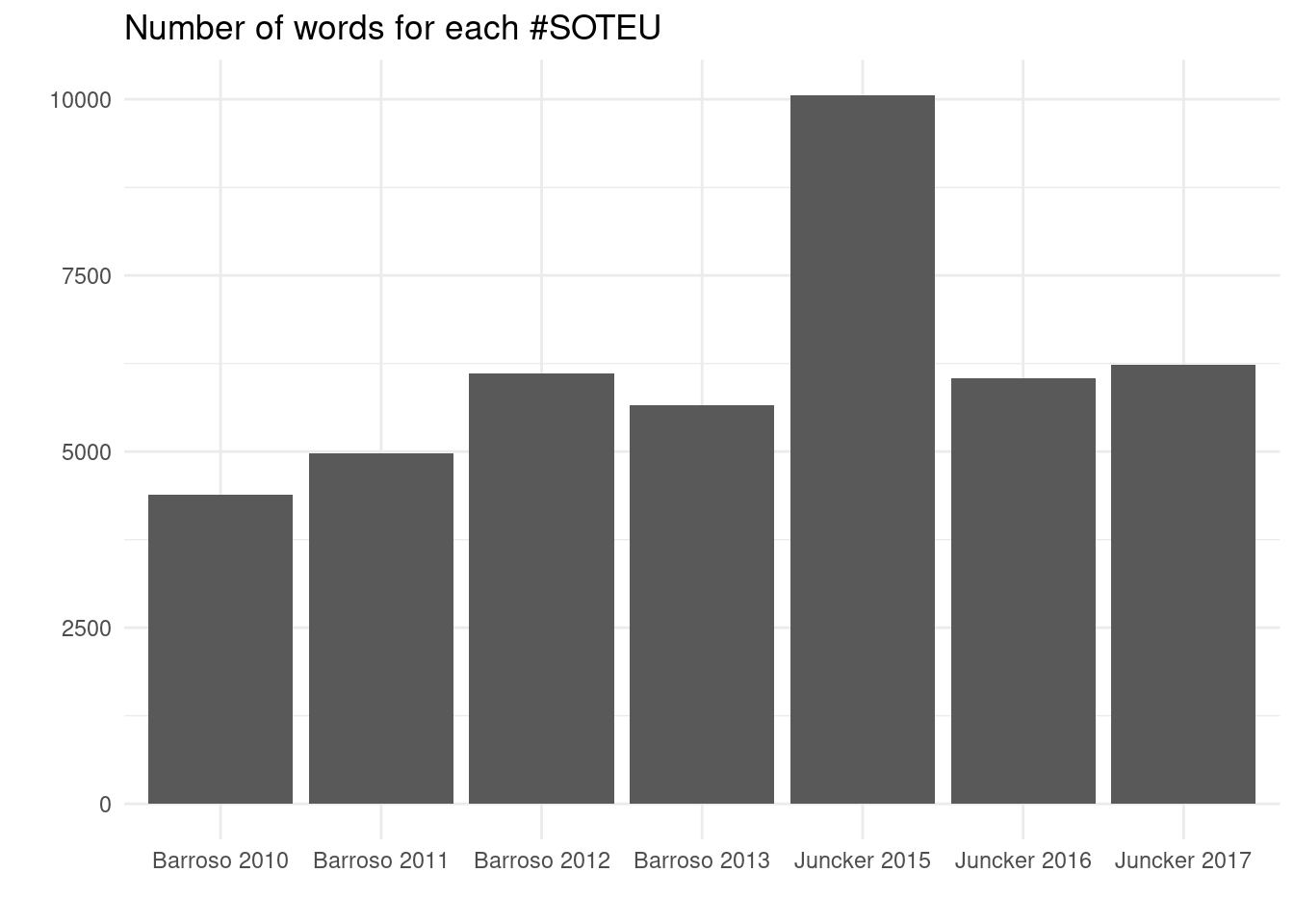

Not all #SOTEU have the same length

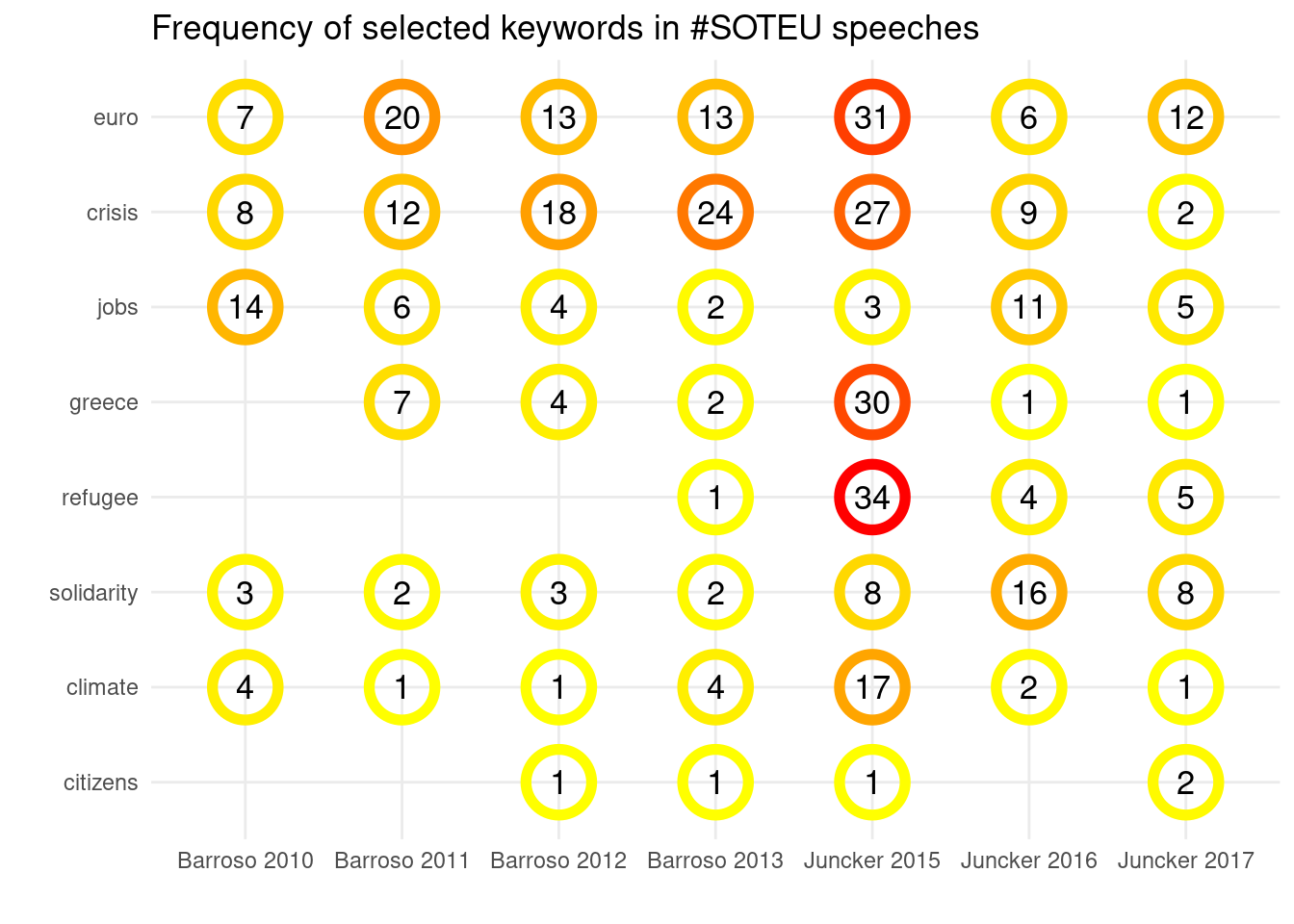

In particular, the fact that the speech Juncker gave in 2015 was substantially lenghtier than the others should be kept in consideration when looking at some of the figures below.

| id | n |

|---|---|

| Barroso 2010 | 4381 |

| Barroso 2011 | 4977 |

| Barroso 2012 | 6108 |

| Barroso 2013 | 5658 |

| Juncker 2015 | 10056 |

| Juncker 2016 | 6041 |

| Juncker 2017 | 6232 |

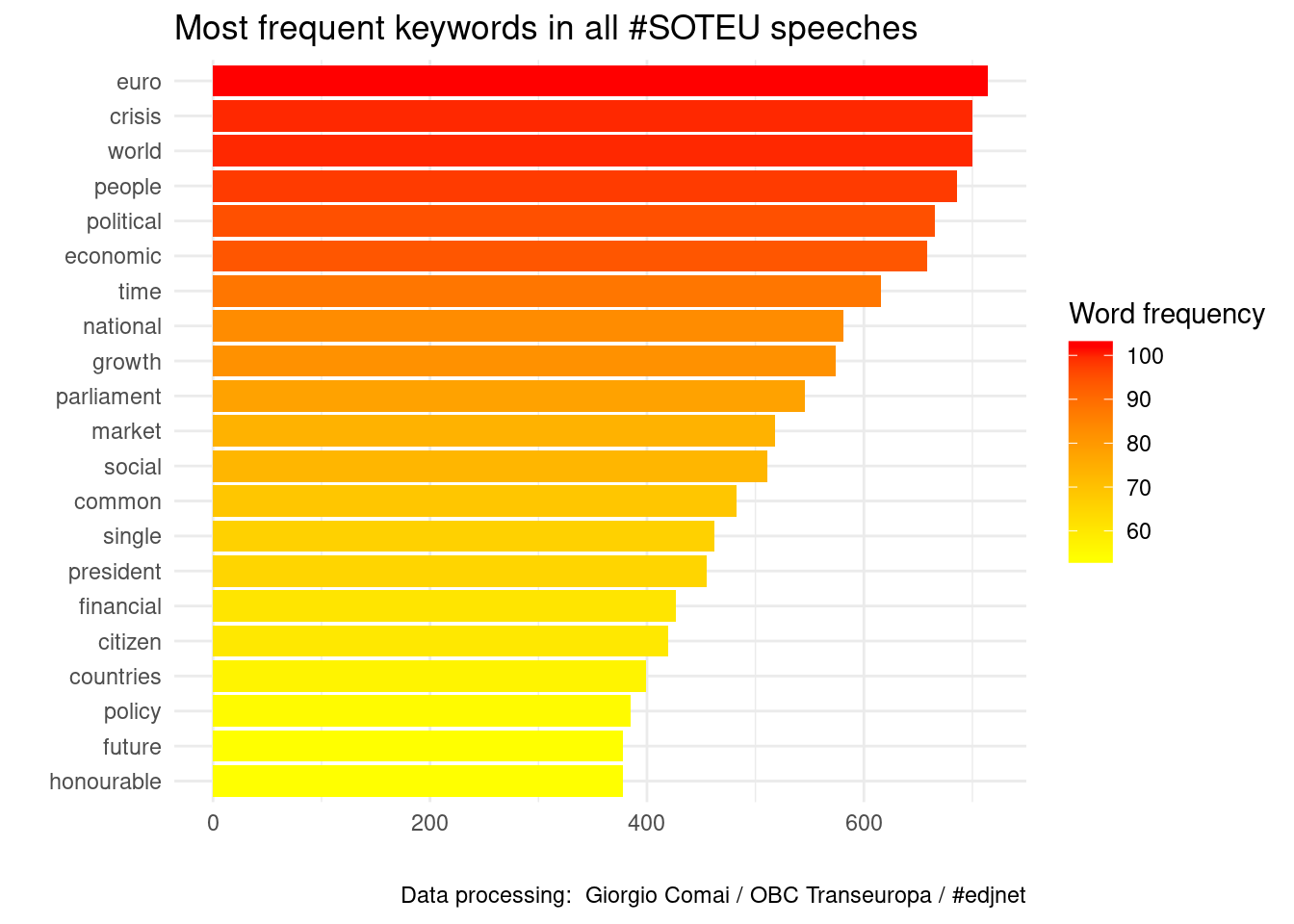

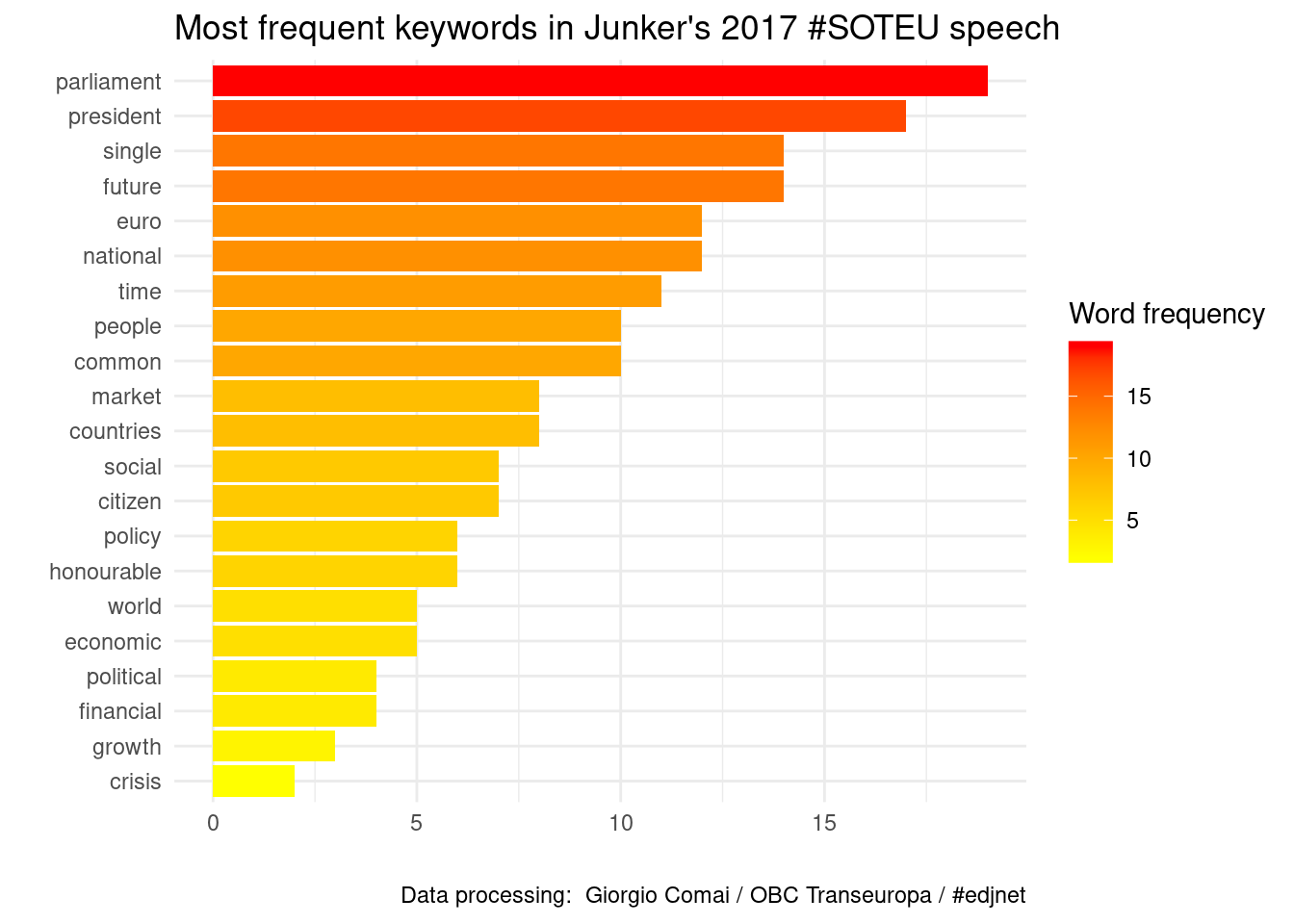

What are the most frequent keywords across all speeches

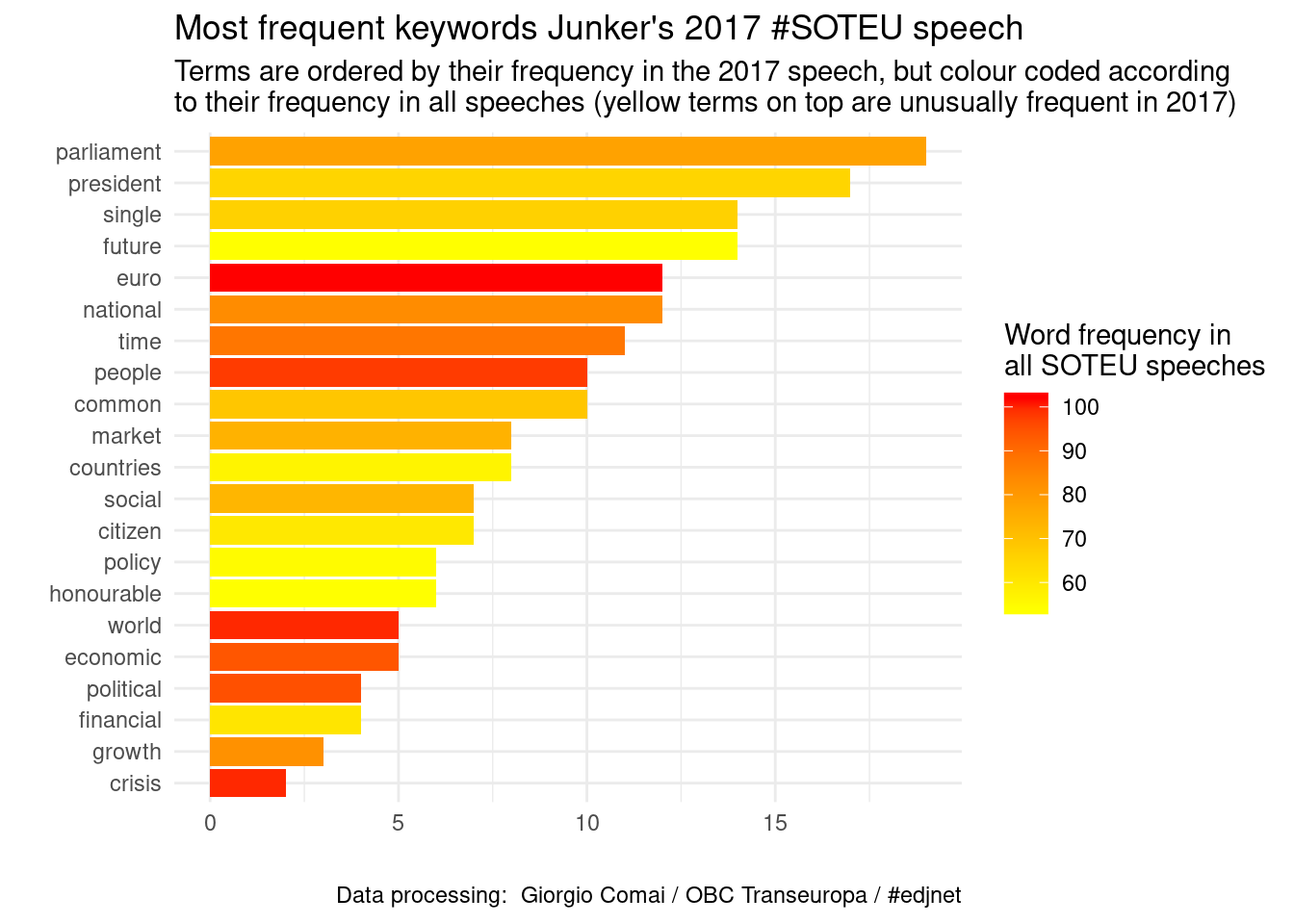

Here are different ways to look at the words most frequently found in all SOTEU speeches.

What are the most distinctive words of each SOTEU speech?

The following wordcloud compares the frequency of words across speeches, showing the words that are most frequent in each of the speech and are at the same time less frequently found in other speeches.

Words with positive/negative connotation

The following wordclouds highlight the frequency of words which have a positive and negative connotation according to the lexicon by Bing Liu and collaborators.1

Looking at these wordlcouds, it quickly appears that ‘crisis’ is the dominant negative words in each of the speeches, but the positive counterpoint is different every year.

Thematic wordcloud

This wordcloud is based on all words included in the same sentence as a given keyword (in this case, crisis).

License

This document, the graphs, and the code are distributed under a Creative Commons license (BY). In brief, you can use and adapt all of the above as long you acknowledge the source: Giorgio Comai/OBC Transeuropa/#edjnet - https://datavis.europeandatajournalism.eu/obct/soteu/.

Yes, clicking through their webpage feels as if entering a time warp, but Bing Liu’s dictionary is widely used. He recently published ‘Sentiment Analysis: mining sentiments, opinions, and emotions’ with Cambridge University Press.↩